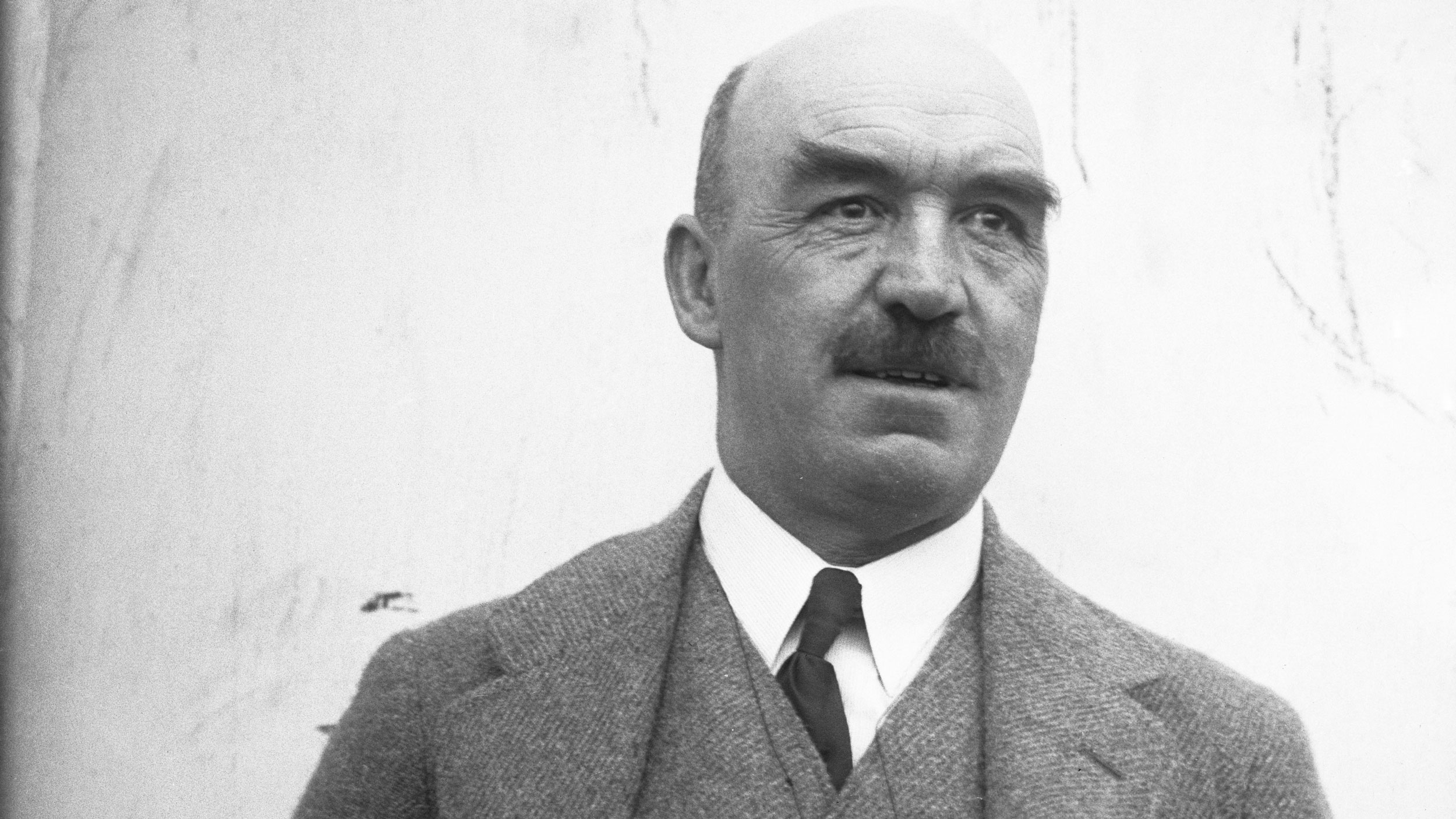

Dr Alister MacKenzie: A Profile Of Augusta's Designer

Yorkshire-born MacKenzie designed many great courses around the world including Augusta National

When the world’s best golfers arrive at the majestic Augusta National each year for The Masters, they tread fairways and fire into greens created by a Yorkshire-born Scot called Dr Alister MacKenzie. Between 1907 and his death in 1934 he became one of history’s most skilful and prolific golf course architects.

Born in Wakefield, Yorkshire in 1870, MacKenzie attended Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in Wakefield then Cambridge University from where he graduated with degrees in chemistry, medicine and natural science. He joined his father’s medical practice but was soon called away to serve in the second Boer War. During the posting MacKenzie developed an aptitude for camouflage – a skill he would go on to use with some aplomb as a golf course designer.

Upon returning from the trenches of southern Africa, MacKenzie briefly went back to his duties as a doctor before embarking on a career in golf course architecture. He was originally inspired to change tack because he was convinced of the benefits golf provided to patients.

"How frequently have I, with great difficulty, persuaded patients who were never off my doorstep to take up golf, and how rarely, if ever, have I seen them in my consulting rooms again." He said.

MacKenzie cut his teeth as a course architect at Alwoodley Golf Club in his native Yorkshire. In 1907 MacKenzie was one of the club’s founding members and, having already made outline sketches for a course, he was tasked with laying out 18-holes across the moorland.

Although this was his first project, the hallmarks of his later works are in full evidence. As he would explain in his book, “Golf Architecture,” MacKenzie believed emphasis should be on the natural beauty of the terrain rather than artificial features. At Alwoodley it’s predominantly the gorse, heather and trees providing protection for the course. The greens are also an early example of MacKenzie’s style – again making use of the natural terrain but sizeable and undulating, testing but fair.

The layout of Alwoodley is principally “out and back,” though not every hole follows this pattern, especially on the front side. Later MacKenzie courses tended to feature two nine-hole loops, to create different wind conditions through a round.

Get the Golf Monthly Newsletter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

There’s an interesting feature around the turn at Alwoodley - from holes 7-11 (off the white and blue tees) you don’t play a par-4. The stretch certainly complies with MacKenzie’s principle that every hole should have a different character. The toughest section of the course is the run back towards the clubhouse. The last six holes play into a prevailing wind blowing off the moors. From the 13th to the 18th there are four par-4s over 400 yards.

After his success at Alwoodley, which is one of the best golf courses in England, MacKenzie didn’t have to look far to find his next commission. He was employed to design a course at Moortown Golf Club, barely half a mile from his first project and another of the best golf courses in Yorkshire. He was struck by the land available and set about creating 18-holes that blended seamlessly into the surrounding heather, pines and birches. The course opened the following year.

The bunkering at Moortown provides an example of MacKenzie’s technique. The traps are links-like, making use of the land’s natural contouring. These may be artificial hazards but they appear to have been carved out of the terrain rather than clumsily thrown in as an afterthought.

The greens at Moortown are large and undulating, again echoing those to be found at seaside courses – a typical MacKenzie trait. He was a great admirer of the Old Course at St Andrews.

Although the term “MacKenzie green” is much used, it’s difficult to give a precise definition of the phrase. MacKenzie’s key philosophy when it came to green design was consistent with his approach to course design in general, ie. - each should appear natural by blending into its immediate surroundings (remember his skills in camouflage.) This meant each putting surface he created was unique. What can be said is, although some are plateaus and others two or three tier, his greens are generally undulating and feature testing borrows.

From 1910 until the outbreak of the First World War, MacKenzie was in high demand and was involved in the construction or remodeling of a number of layouts in Yorkshire and further afield. Among others, these included - Harrogate, Sitwell Park, Reddish Vale, Leeds and Headingley.

After the Great War, during which he received a commission with the Royal Engineers, MacKenzie quickly returned to course architecture and, in 1920, he entered into partnership with another of the day’s great architects - Harry Colt – the association would last until 1923.

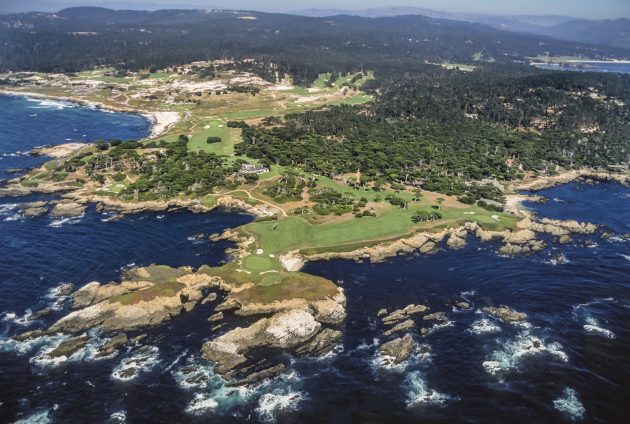

Aerial view of the Augusta National in 1933

Through the early 1920s, MacKenzie was prolific in his design and re-working of courses across Britain and Ireland. One of MacKenzie’s most northerly projects came at The Duff House Royal Golf Club in north east Scotland. Originally designed by James Braid, MacKenzie was employed to redesign the layout in 1923. With it’s lush tree-lined fairways, huge undulating greens and an absence of rough, there’s more than a hint of Augusta to be found here. Bounded by the River Deveron and with views of the magnificent house, this is a course well worthy of that over-used moniker “hidden gem.”

One of MacKenzie’s fundamental principals as an architect was to build courses for the most enjoyment for the greatest number. He believed each golfer should be tested without finding the course an impossible challenge. Nowhere is this more in evidence than at Cavendish Golf Club in Derbyshire. Designed by MacKenzie in 1925 (a private commission from the Duke of Devonshire,) the layout makes excellent use of the natural terrain with each hole delivering a unique and interesting challenge. Although it measures just 5,721 yards, Cavendish provides a suitable examination for even the most accomplished player.

The fact the course has remained virtually unchanged since the mid 1920s gives clear indication of how skillful MacKenzie’s design was. Further evidence of the longevity of MacKenzie’s architectural principals can be found at Littlestone Golf Club, one of the best golf courses in Kent. He was invited to modernize the links in 1922 though some of his recommendations caused controversy at the time. But they were not forgotten and, in 1931, his plans for the 16th and 17th holes were carried through. It wasn’t until 1970 that his intentions for the 2nd were realized and, those for the 3rd weren’t implemented until 1996!

Scarborough South Cliff is another course that remains true to MacKenzie’s ideals. Designed by the great man in 1921, the layout has minimal rough and generous, though tricky, greens. Perched on the cliffs with views towards Scarborough town in one direction and of the rugged coastline in the other, this is a stunning setting for golf. MacKenzie was able to make use of the terrain and the seaside turf to create a course delivering natural beauty and superb variety.

In 1927 MacKenzie travelled to Lahinch in Ireland. His re-design of the famous links is one of the finest examples of his architectural prowess. His use of natural slopes and raised greens created a superb and rugged test of links golf. It’s testament to MacKenzie’s ability as a designer that, from October 1999, the club embarked on an ambitious project to restore the MacKenzie characteristics of the course.

Vast sand hills, terrifyingly quick greens with perplexing contours and run-offs, un-reachable par 5’s and reachable par 4’s, blind tee-shots, blind approaches, tight lies, perilous bunkers and the smell of salt on an ever-present breeze – Lahinch’s variety epitomizes MacKenzie’s ideals for a golf course. It’s unadulterated golf making the very most of the natural terrain, providing a fair test for every standard of golfer. MacKenzie would approve of the sympathetic alterations completed at Lahinch. It’s, perhaps, more than can be said for how he might view modern-day Augusta.

MacKenzie’s Design Principles

In his renowned 1920 book, “Golf Architecture”, MacKenzie speaks of aiming towards the following 13 design principles:

1. The course, where possible, should be arranged in two loops of nine holes.

2. There should be a large proportion of good two-shot holes and at least four one-shot holes.

3. There should be little walking between the greens and tees, and the course should be arranged so that in the first instance there is always a slight walk forwards from the green to the next tee; then the holes are sufficiently elastic to be lengthened in the future if necessary.

4. The greens and fairways should be sufficiently undulating, but there should be no hill climbing.

5. Every hole should be different in character.

6. There should be a minimum of blindness for the approach shots.

7. The course should have beautiful surroundings, and all the artificial features should have so natural an appearance that a stranger is unable to distinguish them from nature itself.

8. There should be a sufficient number of heroic carries from the tee, but the course should be arranged so that the weaker player with the loss of a stroke, or portion of a stroke, shall always have an alternate route open to him.

9. There should be infinite variety in the strokes required to play the various holes, that is, interesting brassie shots, iron shots, pitch, and run-up shots.

10. There should be a complete absence of the annoyance and irritation caused by the necessity of searching for lost balls.

11. The course should be so interesting that even the scratch man is constantly stimulated to improve his game in attempting shots the has hitherto been unable to play.

12. The course should so be arranged that the long handicap player or even the absolute beginner should be able to enjoy his round in spite of the fact that he is piling up a big score. In other words, the beginner should not be continually harassed by losing strokes from playing out of sand bunkers. The layout should be so arranged that he loses strokes because he is making wide detours to avoid hazards.

13. The course should be equally good during winter and summer, the texture of the greens and fairways should be perfect and the approaches should have the same consistency as the greens.

MacKenzie’s Travels

January 1926, MacKenzie left Southampton bound for New York. His final destination was the Californian coast and a new project at Cypress Point. MacKenzie would spend much of the remaining eight years of his life travelling during which time he worked on some of the world’s best-known golf courses.

October 1926 – MacKenzie travelled to Australia and was responsible for the design of the West Course at Royal Melbourne. Upon leaving the continent he left Alex Russell in charge of the project.

The 16th hole on the West Course at Royal Melbourne Golf Club

November/December 1926 – Also in Australia, MacKenzie advised on work to be completed at Royal Adelaide GC and Royal Sydney GC.

March 1927 – MacKenzie was in California and completed his design for the magnificent Cypress Point. Opened for play in 1928 it’s widely considered to be amongst the finest golf courses in the world.

The famous Cypress Point from above

August 1929 – Pasatiempo Golf Club, California. A beautiful layout where MacKenzie made his American home, it still borders the sixth fairway. MacKenzie would die there in 1934.

Autumn 1929 – Crystal Downs, in Michigan. Designed in association with his colleague Perry Maxwell, it has stunning views of Lake Michigan and Crystal Lake.

July 1931 – Bobby Jones had first met MacKenzie at the 1926 Walker Cup and the great amateur developed a profound respect for MacKenzie’s work. He decided the Doctor was the man to assist him in creating a new course in Augusta Georgia.

1933 – Augusta National opens for play and the following year the first Masters Tournament (Augusta National Invitational) is held.

With its creeks, dramatic changes in elevation and fiercely undulating putting surfaces, it has become one of the most recognizable golf courses in the world.

Fergus is Golf Monthly's resident expert on the history of the game and has written extensively on that subject. He has also worked with Golf Monthly to produce a podcast series. Called 18 Majors: The Golf History Show it offers new and in-depth perspectives on some of the most important moments in golf's long history. You can find all the details about it here.

He is a golf obsessive and 1-handicapper. Growing up in the North East of Scotland, golf runs through his veins and his passion for the sport was bolstered during his time at St Andrews university studying history. He went on to earn a post graduate diploma from the London School of Journalism. Fergus has worked for Golf Monthly since 2004 and has written two books on the game; "Great Golf Debates" together with Jezz Ellwood of Golf Monthly and the history section of "The Ultimate Golf Book" together with Neil Tappin , also of Golf Monthly.

Fergus once shanked a ball from just over Granny Clark's Wynd on the 18th of the Old Course that struck the St Andrews Golf Club and rebounded into the Valley of Sin, from where he saved par. Who says there's no golfing god?

-

Rory McIlroy vs Bryson DeChambeau: Who Are We Picking To Win The 2025 Masters?

Rory McIlroy vs Bryson DeChambeau: Who Are We Picking To Win The 2025 Masters?We're set up for a blockbuster final day at Augusta National where Rory McIlroy and Bryson DeChambeau play together in the final group

By Elliott Heath Published

-

The Masters Crystal Rory McIlroy Has Already Won At Augusta National This Week

The Masters Crystal Rory McIlroy Has Already Won At Augusta National This WeekMcIlroy leads going in to the final round at Augusta National, with the four-time Major winner already bagging some silverware before he looks to claim the Green Jacket

By Matt Cradock Published

-

Who Is Bob Rotella? The Man Behind Rory McIlroy’s Masters Run

Who Is Bob Rotella? The Man Behind Rory McIlroy’s Masters RunMeet the person who has become an important member of McIlroy's close team

By Michael Weston Published

-

Are Rangefinders Allowed At The Masters?

Are Rangefinders Allowed At The Masters?Rangefinders are becoming increasinly prominent in the professional game, but what about at The Masters?

By Mike Hall Published

-

What Golf Shoes Is Justin Rose Wearing At The Masters?

What Golf Shoes Is Justin Rose Wearing At The Masters?The Englishman has been seen wearing a number of shoes throughout his career and, at the start of 2025, Rose has been spotted donning footwear from PAYNTR Golf

By Matt Cradock Published

-

The Masters Has The Green Jacket, But Which Other Pro Golf Tournaments Offer Jackets To The Winners?

The Masters Has The Green Jacket, But Which Other Pro Golf Tournaments Offer Jackets To The Winners?It's not all about the trophy and the prize money - there are some nice (and no so nice) jackets up for grabs

By Michael Weston Published

-

What Does 'E' Mean In Golf?

What Does 'E' Mean In Golf?If you're a new golfer, you might be wondering what 'E' means on the leaderboard

By Michael Weston Published

-

Who Is Aaron Rai’s Partner?

Who Is Aaron Rai’s Partner?PGA Tour pro Aaron Rai's partner made a big impression in the 2025 Masters Par-3 Contest, but who is she?

By Mike Hall Published

-

What Does The Masters Logo Represent?

What Does The Masters Logo Represent?The Masters logo is familiar to golf fans around the world, but what does it represent?

By Mike Hall Published

-

Jose Luis Ballester What's In The Bag? 2025 Update

Jose Luis Ballester What's In The Bag? 2025 UpdateTake a look inside the bag of Spain's Jose Luis Ballester

By Matt Cradock Published