US Masters – The Greatest Show on Earth

With the season's first Major, the US Masters, now on our doorstep, Bill Elliott looks back on the history and how European golfers once dominated at Augusta

Whatever else Augusta, Georgia is, it’s a trip. Not just a trip in the sense of car-airport-security-plane-airport-more security-another car-hotel-bar-bed journey from here to there but a trip in the old, sixties, hippy, happy sense of the word. By this I mean that Augusta and the Masters is fantastical and uncommonly absorbing and that it often offers us golf as truly compelling sport. It is also wildy, socially hectic during this particular week. This anyway is how the Masters has been for me since I first arrived wide-eyed in Augusta in 1980. Oh, and bits of it can be a bit irritating.

Seems like last week since I first drove into town, but truth is that much has changed in those 35 years. Superstar golfers have come and gone as has the Berlin Wall, significant journalists too. President Obama, an enthusiastic golfer himself, is in the White House these days but in 1980 the only black guys at Augusta National Golf Club were either hauling clubs round, serving drinks or clearing tables. Few amongst us thought anything strange about such a state of affairs. Times have pleasingly changed for the better.

The course too has been altered radically in tone and length. Sometimes this has meant that the recent Sunday excitement has been a bit muted as players nervously pondered the extra length over a back nine that can cripple as easily as it may enchant, but always there is at least the hovering suggestion that something special may be about to happen. And occasionally it does, at least often enough to keep the legend alive.

Great viewing...

For the big majority of you the Masters is about a weekend set aside for serious television viewing and a late Sunday night before the reality of Monday morning kicks in. For me, it has been about renewing old friendships, visiting old bars and in between these missions wanderingdown once more to the centre of the green cathedral otherwise known as Amen Corner.

A journalist called Herbert Warren Wind came up with this tag for the lowest part of the course where Rae’s Creek meanders like a particularly indolent snake coiling itself around the 11th, 12th and 13th greens. Wind, an old-style and rather arch American, wrote elegantly for the New Yorker magazine – a long-time haven for all things elegant and intellectual and quite often blazingly smug – and it was he who summed up the difficulties of this three-hole stretch by suggesting that any sensible player muttered ‘amen’ if he got out alive or at least didn’t drop too many shots during this exiting process.

Get the Golf Monthly Newsletter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

There really is no finer place to watch sublimely gifted golfers anxiously pitting their wits against Dr Alister Mackenzie’s masterpiece, and although I won’t be there this year and I’ll miss it, I won’t miss it quite as much as once would have been the case. Of course, the Masters is still a must-see event if you haven’t been, but these days the hype is a little overblown for some of us who preferred the older, ever so slightly rougher and certainly calmer-round the-edges Augusta that we first encountered. That’s life I suppose. Rose-tinted glasses always improve the view, especially when azaleas and dogwood are involved.

What is beyond dispute is the thought that the Masters has done more than merely puff out its chest over the last several decades, during which period it has routinely rewritten the rules as to what constitutes an important golf week. How and why the Masters was elevated to its present position as one of the game’s four cornerstone weeks offers a masterclass in self-promotion. Some might call it illusion over reality.

There are many factors in play here. Principle amongst these is, as ever, timing – the Masters heralding spring as effectively as an Easter Egg on a supermarket shelf and perhaps slightly more profoundly. Throw in a spectacular course, the advent of colour television, Arnold Palmer’s suggestion 50 years ago that it was indeed a Major event, the whole Bobby Jones heritage shtick and some very, very smart marketing men who happened to be members and you had an irresistible force that relentlessly lifted this quiet and exclusive corner of Georgia into the global consciousness.

The rest of us may only admire the vision and bravado of Augusta National’s driving members. Clearly, this club was never a sow’s ear to begin with, but somehow the custodians of those Green Jackets have leapfrogged over the silk purse stage of development and turned the Masters into one of sport’s holy grails. A bit sleight of hand maybe, but brilliant nonetheless.

Before the great makeover in the sixties, the Masters was, yes, relevant but not actually hugely important. It was mostly an exclusively American institution and only the most serious of the game’s aficionados around the rest of the world took that much notice of it. Many of our stars, such as Henry Cotton, routinely declined invitations to attend because it was too far and too expensive to travel and the prize money was not that much. At one point the interest level sagged so low that young soldiers from the town’s Fort Gordon training camp were allowed free entry just to add some bulk to the crowd.

It hasn’t been like that for decades now. People who know nothing about golf – and could not care less – desperately want to attend the Masters and they are willing to pay big bucks for a ticket and a room, any room, in the overcrowded town for that week in April. It is now a world event, an aspirational place to see and definitely a place to be seen.

Even before we developed our own inane celebrity culture, the Masters was being celebrated. Claiming you’ve been to a Masters is an acceptably proud boast and one that encourages real envy in a clubhouse or pub; claiming you’ve actually played the course ups the ante and establishes you as something of a mover and shaker in this daft, impressionable world. All good, expensive, daft fun, of course.

Back in the day... By the time I made that first trip 35 years ago, Augusta’s April week was an increasingly serious part of our own sporting calendar on this side of the Atlantic. Television offered anyone who cared to tune in a ride through the technicolour dreamscape or at least the back-nine holes. Until recently TV cameras were not permitted to show all of the front-nine holes as the club felt this stretch should be partly held back for the exclusive enjoyment of the punters, sorry, ‘patrons’, who had paid money to be physically present. Quaint, nice and, while it lasted, sensationally shrewd once again.

Just as Augusta National’s springtime scheduling has been crucial to its turbo-charged, if inflated, development over the last several decades, my own timing turned out to be exquisitely, if accidentally, on the button. Nine months earlier Seve Ballesteros had won The Open Championship at Lytham. He turned 23 at the Masters that week in 1980 and celebrated this happy fact by winning. Young, handsome, gifted, Spanish and exciting he fitted into Augusta’s glamorous folklore as though born for such a role. Which,in many ways, he was.

No-one ever has buckled their swash quite like Seve and his victory claimed miles of column inches in the British newspapers. Ironically, the Spanish papers all but ignored this win although a message to Seve from the king of Spain that Sunday evening was something of a small consolation for a man who never had to trip over it to swiftly recognise any sort of slight.

While Ballesteros was making his triumphant way over the back nine, Jack Nicklaus came in to talk with the media. Now Jack likes to talk – back then he also liked to bum a cigarette off any journalist while doing so – and the main gist of his discourse in 1980 was that his record of five (at that time) Green Jackets would now ultimately be consigned to history because Augusta was made for Seve and he would definitely win more Masters than anyone. Of course it turned out that Seve won only one more, three years later in 1983.

What Nicklaus didn’t say was that Ballesteros had broken through a big barrier with this victory and that the rest of the better European players could now take heart from this win. What none of us knew, what none of us could even dare to hope, was just how much heart these other Europeans would take when Seve walked away with that blazer.

This soon became evident as the chaps queued up to win at Augusta and the European era began in earnest. These were invigorating, exciting times and they helped to change everything for the better for the European Tour as well as golf generally outside the USA. The good times weren’t here yet, but they sure as hell were coming.

European Invasion... Over the next 20 years six Europeans were to win the Masters 11 times. Eleven! And a slice of heaven if you weren’t American. It was the most dramatic of domino effects and without Seve and his determination to triumph at Augusta I doubt much, perhaps any, of it would have happened.

The fact is that Seve liked Americans well enough – especially, it must be said, the women – but he did not like the instinctive arrogance so often displayed by too many of that nation’s golfers at that time, and he saw Augusta National as the natural epicentre of all things American and golf-related. Closer to a shrine than merely an ultra-exclusive, blindingly rich, white golf club with an impossibly pretty course, Augusta screamed superiority.

Except that being Augusta there was no screaming, just a quiet expectation that we would all acknowledge its excellence – which, of course, we did. If Seve was to lay down a marker that there was golf, great golf, to be found outside the States then this was his preferred place to do just that. His winning the 1980 Masters was the result of a personal crusade, not just a stunning reward for high ambition and naked skill.

His high delight and optimism when a few of us joined him at his rented house for a celebration that first Sunday night was both clear and infectious. “This is the beginning, only the beginning. Not just me but others from Europe will know they can win now. You watch. What I say is true,” Seve told me that evening. Then he walked me to the trapeze-like contraption he had installed in a doorway and encouraged me to hang upside down, just as he had to do each morning to ease his aching back. Even back then he feared that he faced the probability of a truncated career.

A second victory in ’83 for Ballesteros suggested that Nicklaus’s prophecy of a record-breaking total of Masters before he finished was more nailed-on than fanciful. That it didn’t turn out this way was down to several factors, but most notably that misaligned spine and the shock of chunking a simple enough shot into the water at the 15th hole in 1986 to allow, yes, Nicklaus to step in and win his sixth Masters instead. A fortnight after that error I met Seve in Madrid and asked him, now he had had time to reflect, what had happened on that fairway and on a hole he liked.

He looked at me for what seemed a long time and then quietly admitted that he had no idea. “I don’t know, I just don’t know. For me it was just a shot, nothing too difficult, nothing too special. It was not easy, but also not that hard. I have thought about this mistake and I still don’t know the answer.” And I saw what I took to be a flicker of fear in his eyes because he knew that if this error had arrived once out of a clear, blue sky then it could spear him again when he least expected it. He finished tied for second the following year, but there were to be no more victories in Georgia. The great leader, however, had than done his job.

Behind him the rest of European golf’s small posse of potentially great players had taken note of his success and raised the bar on their own expectations. Now that Seve had cracked Augusta, Sandy Lyle, Nick Faldo, Bernhard Langer and Ian Woosnam knew they also were entitled to contemplate success there. Meanwhile, a younger Spaniard, Jose-Maria Olazabal, was paying close attention. Before the 20th Century ended, each of these men was to succeed in this quest and world golf was never to be quite the same again.

Langer was the first of Ballesteros’ peers to react to the Spaniard’s charge through America’s favourite backyard. The first of Langer’s two wins came in 1985 and in many ways his was the most surprising triumph. The German, after all, had been sporadically suffering from the putting yips for several years. At times, this awful affliction reduced him to tears of frustration. For him to win at Augusta where the greens are acknowledged as the most challenging in the world was as perverse as it was terrific. First, though he had two other obstacles to overcome on that final Sunday in ’85.

A committed Christian then as now, Langer and his American wife Vikki headed off to church to pray that Sunday, but for some inexplicable reason their usual church in Augusta was locked and the surprised pair were forced to return home to pray. If that was unsettling, Langer knew that a potentially even more unnerving challenge awaited him at Augusta National when he teed off around two o’clock that afternoon for fate had decreed that he would be partnered by none other that Seve.

A year later as I helped him write his autobiography, Bernhard told me: “I had finished the third round two strokes behind Raymond Floyd, one adrift of Curtis Strange. More significantly, I was tied with Seve. Significant because Seve was a difficult man to partner. We were different sorts of people when we played. I like to be friendly, to talk with my partners during a round. Seve, on the other hand, preferred to say little or nothing. He was so intense out there it was unbelievable. If he did not think it was a great – a truly great – shot he didn’t say anything. I found this attitude off-putting and so I knew it was going to be an even greater challenge playing alongside him.”

The pair wished each other luck on the first tee and the next time Ballesteros spoke to Langer was as they stood on the last. By then, Bernhard was two shots clear and he felt a tap on his back and when he turned, Seve simply said: “Well done, this is your week.” They are words that resonate still for Langer. What resonates slightly less pleasingly is his decision that final day to wear a pair of red trousers that clashed terribly with the Green Jacket he ended up having slipped over his shoulders. “No, I did not think that through properly, “ he admits and a rare example of this carefully considered man missing a trick.

Two years later Lyle was the victor. The amiable Scot played some of the very best golf of his life that week in Georgia, his drives finding the correct placement on the undulating fairways, his approach shots slipping quietly on to greens and his ball rarely more than 20ft away from its target.

Of course, he was also required to come up with a sublime 7-iron out of a fairway bunker at the last, his ball thumping into the green above the hole before trundling back down to set up a clinching birdie. This was a shot and a result that was forecast by Lyle’s great rival Faldo as the Englishman, his own Masters over, joined the TV commentary team to cover the last few holes. Faldo was gracefully courteous in his public congratulations to Lyle, but inside he was building an irritated determination to follow the Scot’s example at a Masters.

Three years earlier he had embarked on a courageous, some thought foolhardy, mission to totally rebuild his swing under the narrow scrutiny of David Leadbetter. He did so because his old swing, good enough to win him much in Europe, had broken down under pressure at, yes, Augusta. In 1987 I bumped into Faldo at Atlanta airport. I was waiting for a flight to Augusta, he was heading off to Palookaville and some minor event. It was the second year he had not qualified for the big week and, as it turned out, it was to be the last.

That summer he won his first Open title and in ’89 he followed up Lyle’s Masters win with his own victory. Okay, Scott Hoch had to miss a two-foot putt during their play-off, but there was no doubting the fact that the Faldo era truly had begun.

When he successfully defended the following year and when Ian Woosnam won in 1991, it meant four successive Masters falling into British hands. The Americans were as confused as they were upset about this turn of events. It meant that Woosnam had to withstand some crude heckling from an upset crowd at times during his Sunday round with Tom Watson. Naturally, this heckling stuff only made the pugnacious Welshman even more determined to win the Green Jacket.

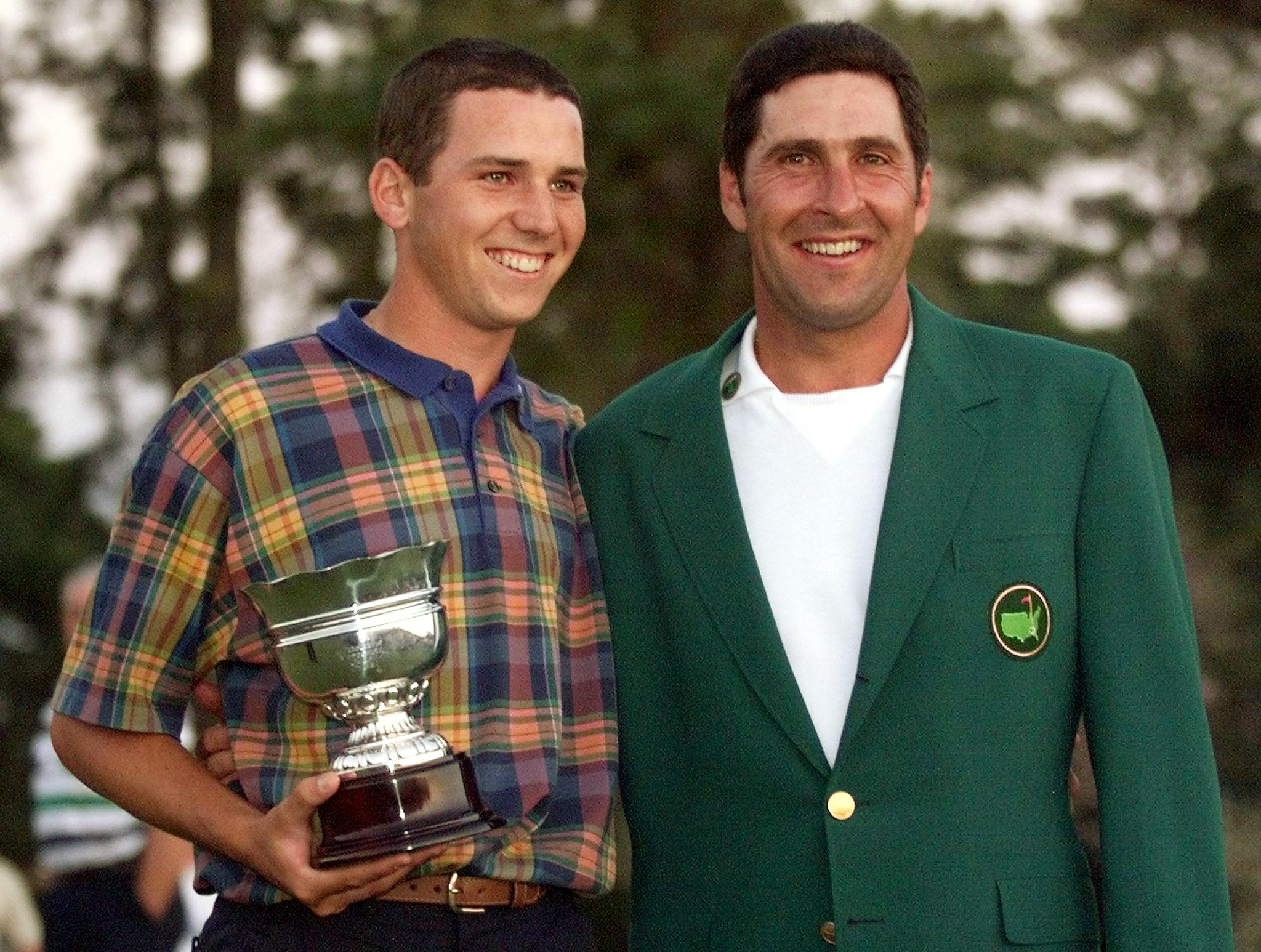

Ollie, Ollie, Ollie... Three years later Olazabal joined the party before in 1996 Faldo won one of the most celebrated victories when he overcame a six-shot deficit to Greg Norman during an astonishing final round. In 1999 Olazabal completed his comeback from injury and illness with his second win. Astonishing though it is, that has been it for Europeans.

A glorious romp, but who would have imagined that we could get 15 years into the 21st Century without a victory for Europe? Factor in the thought that Europe’s strength in depth during this period has been the strongest in the game’s history. Probably, I suppose, just another example of the old game’s eternal predisposition to embrace perversity and stamp all over anything even vaguely logical.

Of course even the most unpredictable of the game’s gods will struggle to deny Rory McIlroy his moment in the Georgia sun sooner or later. It may be asking too much for him to prevail this year and so complete his Grand Slam at a ludicrously young age – although this doesn’t stop us asking and hoping – but surely he must win at Augusta before he is finished? Mind you, many of us thought the same about Norman and look what happened to him.

No-one, of course, knew more about golf’s ability to enchant and confuse than Augusta National’s creator and the most iconic of golfers, Mr Jones. His vision was to build a course so good, so attractive that no-one would refuse an invitation to attend the annual competition he envisaged to celebrate the game that had made him one of the most famous men in America and beyond. Originally he intended to build this place in, or close to, his native Atlanta.

But when he saw the plant nursery that Augusta National originally was, he fell in love with this unique piece of real estate. Not the biggest of men, he had to stand on an upturned toilet bowl to see it properly first time he visited the site. Why a toilet bowl? Because before Jones arrived on the scene the plan had been to build a hotel on this land and the infrastructure for this abandoned project was scattered around.

When the club was being formed in 1931 the original business plan called for 1,800 members paying 60 dollars each a year. In 1934 as the first ‘Masters’ took place – it was called the Augusta National Invitation Tournament back then – the club was just 1,724 members short of that original goal. Several times over the next couple of decades the place almost shut down. In 1946, for example, the winner, Herman Keiser, was told that his silver trophy would be sent on to him just as soon as the club came up with the money to purchase it.

The genius behind Jones and the eventual growth of the Masters was his co-founder, a businessman called Clifford Roberts and a man who became obsessed with the growth of the Masters and who was chairman until his death in 1977. Peter Dobereiner, famed golf correspondent for The Observer, knew Roberts well and once wrote that Roberts was determined that “everything about Augusta National Golf Club and the Masters had to be the best and if it was not the best then it would have to be improved every year until it was”. It is an ambition that prevails to this day.

This determination to be better than anyone or anywhere else is two-sided of course. On the one hand it means that each year of the 34 that I have attended a Masters there has been some improvement to the place, to the course or to both. Sometimes these advances are subtle, sometimes they are obvious, but they never stop taking place. There is, frankly, nowhere like it in golf or indeed in the general world of sport. The downside is that this ‘better-than-you’ philosophy can sometimes encourage an arrogance that can irritate those on the receiving end.

That’s entertainment... Always, however, the way the game of golf is delivered to a watching world during Masters week overcomes most, if not all, of anyone’s misgivings about the place. The great duels over the years, the battles between Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer, the European surge, the arrival with trumpets and rockets of a young Tiger Woods, all these and more flare in the imagination.

Golf at Augusta National is the game as it would always be portrayed if we only could arrange such a thing. But we can’t and so this most gorgeous of killing fields has become the template for something close to perfection. Jones’ big plan was to build a club that celebrated everything that he saw as terrific about golf. Roberts’ drive and attention to detail pretty much delivered this dream.

Much, if not all, of this back-story will be lost on many of the young professionals who stride onto those immaculately prepared fairways for this year’s Masters. Oh, they will have a vague notion of why and how the Masters has managed to weave its way into a curious global consciousness, but not much. Until they grow older and begin to appreciate the relevance of history to our appreciation of the now, this is how it should be. Jones and Roberts, I suspect, would not have minded this ignorance.

Instead, they would concentrate on the happy thought that while there are more demanding, more dynamic sports than daft, old golf, the Masters sensationally confirms the thought that, actually, none are quite as beautiful. When this 2015 version concludes, the serious-faced men of Augusta will sit down once more to try to work out how to make it even better for next year.

Shortly before they do this, they will have the gates shut to anyone not a member or their guest and invite the rest of us to go to hell for another 51 weeks. As ever, they will do this firmly and politely. We won’t mind. They know and we know that it is all part of the game. At least the game as played at Augusta.

-

Volvo China Open 2025 Picks, Odds And Predictions

Volvo China Open 2025 Picks, Odds And PredictionsFollowing a break for The Masters, the DP World Tour returns for the final two weeks of its Asian Swing and the Volvo China Open is the penultimate event

By Jonny Leighfield

-

Rory McIlroy's Sports Psychologist Explains Why He 'Didn't Talk' To Bryson DeChambeau In Masters Final Round

Rory McIlroy's Sports Psychologist Explains Why He 'Didn't Talk' To Bryson DeChambeau In Masters Final RoundDeChambeau raised eyebrows at Augusta National when claiming that McIlroy wouldn't engage in conversation during the final round of The Masters

By Jonny Leighfield