'Golf Saved My Life' - Amazing True Story About Overcoming Drug Addiction

Recovering drug addict Kevin Perry credits golf with bringing him back from the brink. He tells Michael Weston his remarkable story...

Recovering drug addict Kevin Perry credits golf with bringing him back from the brink. He tells Michael Weston his remarkable story...

'Golf Saved My Life' - Amazing True Story About Overcoming Drug Addiction

A biting wind whips through the valley, cold enough to make your teeth chatter.

Down on the tee, a roll-up is about to get underway. Even from a distance, you can see shoulders moving up and down and hear the guffaws as pleasantries are exchanged.

It might be more comfortable in the warmth of the clubhouse, but Kevin Perry would do anything to be outside facing the elements and sharing a joke with his fellow members.

For the recovering drug addict, this is what the game is all about. Surrey National is his sanctuary. If only he could play more often.

When Kevin was three years old, he was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a debilitative condition that causes muscle weakness and fatigue. It went into remission when he was 11, but school – and later, college – were a constant challenge.

Get the Golf Monthly Newsletter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

“You want to be doing all the things that the other kids are doing, and I couldn’t do that,” he says. “I couldn’t run. I’d go 20 metres and start panting. Things were taking me three times as long to learn. I couldn’t walk upstairs, or open a car door. It created a problem that I didn’t really know how to deal with.”

Downward spiral

After breaking up with his girlfriend, Kevin found himself out of control. He was determined to instigate his own downward spiral. Nothing was going to stop him.

When he was 17, he started taking heroin and crack cocaine. At first, he clung to the hope he could drag himself back, because he knew that what he was doing was wrong – but he soon became addicted.

His medical condition is tough to explain, although speaking about the next period of his life causes greater anguish.

“I was living on the streets,” he says, sighing heavily. “I was sleeping outside Morden tube station, wherever... people’s houses. I’d fallen out with my parents because I’d stolen from them [for the addiction]. I’d treated them like s**t. They’d had enough of it – rightly so. All the time I was on it, it was terrible for them. They suffered, but the minute you start showing you want to do good, they were there.”

And Kevin did want to do good. It was the first step. In 2004, he went to Springfield University Hospital to commence detox – a “crazy” period. “It’s like that film, Trainspotting,” he says with a grimace.

“It’s the nearest you’ll get to the wildness of it all. It’s disgustingly bad. There’s no way out of it. You’ve got to suffer. When I went in, I took this camera, and they were like, ‘Why have you got that?’ I said it’s because I never want to come back. I want to be able to look at it and go, ‘That’s that.’”

Turning things around

Kevin has now been clean for 16 years. He pauses and takes a deep breath. Describing the next stage of his recovery requires a great deal of effort, so he moves attention to a piece of silverware he’s brought along – the ‘Blue Bogey’ trophy. Fonder memories.

Kevin shot 80 off a 14 handicap. Forget the RS Turbo he owned when he was a teenager – he liked his cars – this is his real pride and joy; it’s “the most fun” he’s had.

Kevin turned his life around at rehab, yet his mid-20s are riddled with painful memories – injections, sickness, scars... worse. Among those images, he remembers the first moment he laid eyes on Thames Ditton and Esher Golf Club, which came as he sat in a car with his dad waiting to check into rehab.

“It’s mad,” he says, with a shake of the head. “He’s moaning at me saying all the things you’ve got to do. I’m looking out the window and I’m like, ‘there’s a golf hole!’”

It would be the escape he needed to help stay on the straight and narrow; offering some peace and quiet away from the house he shared with nine other recovering addicts.

He puts his trophy to one side and opens a photo album. Rehab. At a glance, everyone looks happy, arms around shoulders, people holding funny poses. “I can tell you, they weren’t happy,” he says. “Stupid boy. Look how skinny my arms were, the scars.” He wipes his eyes.

Other pictures provide some light relief, happier tears. Kevin with his cars, a camping trip with his housemates, “potholing and rock climbing with a bunch of lunatics,” he laughs.

Pictures of Dave, who became a close friend, evoke many fond memories and no small amount of regret.

The day he arrived for rehab, he spotted someone walking out the house with a set of golf clubs. Rules prevented Kevin from going out on his own at first, unless in the company of someone who had been in the house for two months. Not long later, his dad returned with some old sticks from a car boot sale, and that was that – Dave was his golf partner.

“That was something special,” he smiles. “Whenever we could get out, we would. Some mornings the only way you could find your ball was to follow the marks in the dew into the undergrowth. I did hit some good shots back then, but I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. The game just sucked me in. I was as fit and healthy as I’d ever been.”

Kevin left the house after eight months. He didn’t finish the programme, but he describes his time there as a “100 per cent success”.

“I wasn’t learning any more and I needed to get out and see if I had the tools in the real world,” he explains. “The next day I went to work. I had two mates who were plasterers and I rang them up the day I was leaving. I said, ‘Have you got anything?’ and they said, ‘See you at 9 o’clock in the morning.’”

Kevin stops, because it’s at this moment in his life when he began his second chapter. Not everyone found a way to start afresh. Dave died of an overdose.

Despite wanting to put the past behind him, Kevin retains a letter from his friend, one that wishes him a healthy future. “He was a lovely bloke” he says. “He didn’t make it. A few of them have gone. At least I’m here to tell the story.”

Slow road back

Piece by piece, Kevin put his life back together. Hampered by fatigue, he found nine holes on the weekend was good for the mind, if not the body. He recommenced his love affair with the game at the Oaks Golf Centre near Sutton, where he joined up with some old friends.

It was a relief to be out on the fairways again, although it wasn’t until he joined Surrey National four years ago that he began to take the game seriously. This is when “the good stuff started”.

“I joined here on my own,” says Kevin, now 41. “I told people my story. I don’t shy away from it. Everybody loves a game of golf. It doesn’t matter about your background. People are very open now. If you love the game, people like you. Chris, the manager, has always looked after me. Keiran Smith, the pro... they’re all really supportive.

"There’s nothing that would have got me like this. It’s the rules that you’ve got to adhere to. There are so many things like that that can help you in life. If you can respect the game of golf, you can respect people in life.”

Saturday at Surrey National – nowhere is Kevin happier. Even better, out with his regular Swindle, the Pistol Knights. “I can’t get enough of it,” he laughs. “They’re all great. Now [February] is not the best time for me because I need a buggy and I can’t go out on the grass until April.

"Sometimes I can only do four holes, sometimes nine. Sometimes I can do 18, but I like to come up here, it gets me out the house.

“I stay up here after a game for a couple of hours just chatting to the lads. We have sporting events and bbqs in the summer. It’s like a pub on a Saturday. I don’t think I’ll ever get bored of coming up here. This is my home. If I couldn’t play anywhere else again it wouldn’t bother me. I’m happy here, as much as I would love to go and play Augusta.”

Kevin is looking outside now. All this talk has got him itching for a game. He’s well and truly got the bug. “I suppose I have got an addictive personality,” he says with a wry smile.

It’ll have to wait. Keen to sharpen up his game for an upcoming Ryder Cup-style match, he’s done something he can’t normally do a lot of – practise. Walking the course now would feel like wading through thick mud, so he takes another cup of tea instead.

“I’ve got something to channel all this into now, which is good for my golf,” he says, as he shows one of the tattoos on his forearm – a star that signifies the time he left rehab. “It’s a bottomless pit this golf. I’m as happy as I can be now. Every week I come up here, I think I’m going to win. I don’t win, but I don’t go home unhappy. As long as I get to come and play golf on a Saturday, that keeps me happy.”

So too does the relationship he now shares with his parents. Overcoming his addiction has made them proud. “Mum and dad were brilliant then, and they still are,” he says.

He prefers not to think what might have happened without their support. What if he hadn’t stumbled across a golf course all those years ago?

“I don’t like thinking about what might have happened. It’s best to keep looking forward.”

Don't forget to follow Golf Monthly on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Michael has been with Golf Monthly since 2008. A multimedia journalist, he has also worked for The Football Association, where he created content to support the England football team, The FA Cup, London 2012, and FA Women's Super League. As content editor at Foremost Golf, Michael worked closely with golf's biggest equipment manufacturers and has developed an in-depth knowledge of this side of the industry. He's a regular contributor, covering instruction, equipment, travel and feature content. Michael has interviewed many of the game's biggest stars, including seven World No.1s, and has attended and reported on numerous Major Championships and Ryder Cups around the world. He's a member of Formby Golf Club in Merseyside, UK.

-

Volvo China Open 2025 Picks, Odds And Predictions

Volvo China Open 2025 Picks, Odds And PredictionsFollowing a break for The Masters, the DP World Tour returns for the final two weeks of its Asian Swing and the Volvo China Open is the penultimate event

By Jonny Leighfield

-

Rory McIlroy's Sports Psychologist Explains Why He 'Didn't Talk' To Bryson DeChambeau In Masters Final Round

Rory McIlroy's Sports Psychologist Explains Why He 'Didn't Talk' To Bryson DeChambeau In Masters Final RoundDeChambeau raised eyebrows at Augusta National when claiming that McIlroy wouldn't engage in conversation during the final round of The Masters

By Jonny Leighfield

-

7 Most Annoying Golf Playing Partners

7 Most Annoying Golf Playing PartnersWe showcase the seven most annoying playing partners that golfers can have the misfortune of teeing it up with!

By Sam Tremlett

-

How To Clean Golf Clubs And Grips

How To Clean Golf Clubs And GripsIf you want to know how to clean golf clubs and grips, check out this step-by-step guide

By Sam Tremlett

-

In Praise Of Golfing In Winter

In Praise Of Golfing In WinterFergus Bisset on why he enjoys playing golf through the winter months

By Fergus Bisset

-

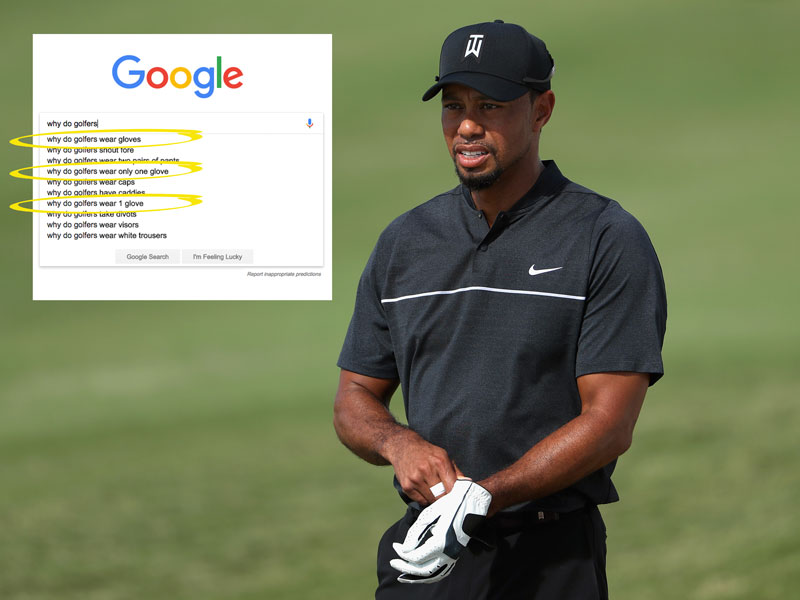

'Why Do Golfers Only Wear One Glove?' You Asked Google And We've Got The Answer...

'Why Do Golfers Only Wear One Glove?' You Asked Google And We've Got The Answer...You asked Google and we've got the answer...

By Roderick Easdale

-

How To Regrip Golf Clubs

How To Regrip Golf ClubsKnowing how to regrip golf clubs means you can afford to replace them as and when they need replacing

By Joe Ferguson

-

The 7 Scariest Shots in Golf

The 7 Scariest Shots in GolfWith Halloween creeping up, we have selected the 7 scariest shots in golf

By Neil Tappin

-

17 Ways To Tell You're Obsessed With Golf

17 Ways To Tell You're Obsessed With GolfThe tell-tale signs that you are a true golf fanatic

By Roderick Easdale

-

10 Of The Best Arnold Palmer Quotes

10 Of The Best Arnold Palmer QuotesHere we take a look at 10 of our favourite Arnold Palmer quotes

By Roderick Easdale