Ben Crenshaw - The Greatest Putter

He was the best player to pick up a putter - but where did Ben Crenshaw's skill come from?

There can be little argument that Gentle Ben was the finest player the game has seen on the greens. But just what made him so good?

It’s a strange hole, Augusta’s 14th. Strange in that it can get somewhat clouded in the memory amid the chaos of Amen Corner, the risk-reward 15th or the par-3 one-shotter at 16 where the cheers echo and reverberate all the way back to the clubhouse. As Masters patrons seek the thrills elsewhere, 14 is often bypassed and yet it is here where many Green Jacket hopefuls have met their match.

So what’s the deal? Its length is consistent with many of the course’s par 4s at 440 yards, and players are asked no real questions from the tee other than to keep their drives to the right side in order to avoid the most subtle of elbows as the fairway turns gently to the left.

On top of this, it is the only hole on the course without a bunker. Some would call it simple; others would call it boring. But anyone who does so is unlikely to have ever set foot on one of the most infamous putting surfaces in the game of golf. As Ben Crenshaw once said: “There has never been another green built like it.”

It was here during a late spring afternoon in 1984 that Crenshaw first etched his name into Masters folklore, fulfilling the talent and living up to the weight of expectation bestowed on him after joining the PGA Tour in 1973. Crenshaw had long been regarded as one of the game’s finest exponents with the flat stick, but his virtuoso display that day remains one of the best the game has seen.

The Texan had already stroked home birdie efforts at eight and nine, before canning one of the longest putts in the tournament’s history with a 60-footer at the downhill 10th. But while that long-range efforts sticks out in the memories of most, the 12-footer he sank on the 14th would prove to be one of the gutsiest par saves of his career.

“He came up short, and he’s got this downhiller, about 12 foot, to make his four,” said Nick Faldo, Crenshaw’s playing partner over the final 18 holes. “It’s one of the quickest putts because it goes up over a very subtle ridge, and then there is nothing left to stop it. It just goes.”

Get the Golf Monthly Newsletter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

But what could stop Gentle Ben? Breaking from the right, Crenshaw – his eyes bulging and his head seemingly locked in a vice-like grip – brushed the putt home with nonchalant ease. Then he turned away, dismissing the green in a manner of defiance and arrogance.

With a three-shot lead tied up, he would card a closing 68 to win by two from Tom Watson. “I knew I was capable,” he would say. “But you never know. You just never know in golf.”

There are many theories as to why Ben Daniel Crenshaw was such a fine putter. He putted with a relatively open stance, which allowed him to see the line better, and relied on an almost effortless stroke to get the ball rolling.

Picking lines was made easier by the fact that he would never force a putt; he respected the break and simply allowed the contours to take the ball on its path, sometimes eyeing up a spot no more than three feet away rather than attempting to cater for breaks further down the line.

With the ball set forward in his stance, his tempo, despite a relatively long backswing, remained consistent and this, even on the speediest of greens, meant he was able to master the art of lag putting with great effect.

His thumbs would sit on top of the shaft, feeling his fingers at the back of the grip. Soft hands would let the putter head come through and do the work, and during the stroke, he would keep those hands in front of the blade at all times.

But what made him great, rather than simply good, was the fact that he focused on feeling at his most comfortable before pulling the putter back. That was his trigger; that was what allowed him to putt so freely while others would fight as the mechanics of their stroke broke down – because with Crenshaw, the mechanics would be secondary.

He putted without tension, and that was the key ingredient. When there was tension, the putter head would become lighter, forcing him to work more with his stroke. Without tension, a premium was put on maximising both rhythm and tempo. It was a beautiful complement.

MEETING HIS MENTOR

Crenshaw was just six years old when he first shook the hand of Harvey Penick, the man who would be his one and only coach – guiding the youngster through the game’s early perils.

Penick’s first love with golf came via his caddying duties at Austin Country Club. By 1923 he had become the club’s head pro at the age of just 19, a position he held with distinction until 1971.

In his later years he became a respected author with the success of Harvey Penick’s Little Red Book, a tome of his instruction wisdom that would go on to become one of the best-selling sports books of all time. Thus, global recognition came late to Penick in 1990, just five years before his passing at the age of 90 on the eve of the 1995 US Masters.

Despite the success of Penick’s published work, it was his relationship with Crenshaw, and also Tom Kite, the 1992 US Open champion, that made him stand so tall in golfing circles. A man of total respect, he was rightly attributed with helping to groove Ben’s game on the greens, but he was also the man to smooth out the flaws in his early swing faults. Together, they formed an unbreakable bond.

EARLY STRUGGLES

While his early years were sprinkled with moments of brilliance, Crenshaw’s inability to close out tournament wins would become a recurring theme throughout the front half of his career. For a man so assured on the greens, his complex character had the critics circling.

The moniker of ‘Gentle Ben’ couldn’t have been further from the volatile young man who, while displaying all the hallmarks of greatness, could also reveal a temperament that would continually let him down. Softly spoken and a gentleman he may now be, but in his late twenties and early thirties, few were as quick to boil. Good or bad, he fed off emotion. That was how he was built.

While the ability to contend was never in doubt, the big win would elude him until that iconic day at Augusta. There are many who will claim he should have won more since, as he was a constant menace on leaderboards throughout the late eighties. And, as a new decade loomed with many players switching to metal woods and neglecting the shot-shaping credentials of persimmon, even more pressure was put on his short game despite him being far from one of the shortest hitters on tour.

Then, of course, there was that temper waiting to erupt. Like at the 1987 Ryder Cup, when, during his final-round singles match against Eamon Darcy, he broke his putter in a fit of pique on Muirfield Village’s 6th hole. Unable to replace the club, he putted first with a sand wedge, and then with his 3-iron, somehow taking the match to the final hole where Darcy was forced to hole a slippery six-footer for victory.

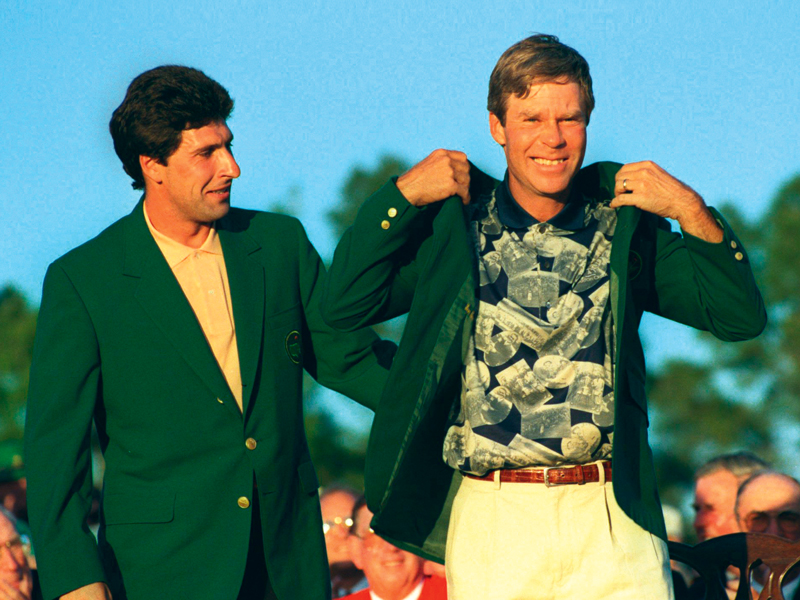

With his career now tailing off, Crenshaw headed to the 1995 Masters as an out-of-sorts 43-year-old. He was by now barely a feature in the Majors, and had only won four times on the PGA Tour that decade. But over the course of the next four days, he executed his game on Augusta’s greens to near perfection.

Tied for the lead with Davis Love III with three holes to play – and with Love in the clubhouse on 13-under-par – he would make birdies on 16 and 17, and with a two-shot lead was able to play the last in relative comfort, carding a bogey for a final round of 68. Through 72 holes and four days, he did not three-putt once.

And that was the last time Ben Crenshaw would win on tour – a fitting finale and a honourable exit from the winner’s podium in a tournament that kicked off less than 24 hours after he had been a pall-bearer at Penick’s funeral. Overcome with emotion, his victory was met not with joyous celebration, but by breaking down in tears for the man who took him there and yet could not be by his side. Perhaps it was just meant to be that way...

Alex began his journalism career in regional newspapers in 2001 and moved to the Press Association four years later. He spent three years working at Dennis Publishing before first joining Golf Monthly, where he was on the staff from 2008 to 2015 as the brand's managing editor, overseeing the day-to-day running of our award-winning magazine while also contributing across various digital platforms. A specialist in news and feature content, he has interviewed many of the world's top golfers and returns to Golf Monthly after a three-year stint working on the Daily Telegraph's sports desk. His current role is diverse as he undertakes a number of duties, from managing creative solutions campaigns in both digital and print to writing long-form features for the magazine. Alex has enjoyed a life-long passion for golf and currently plays to a handicap of 13 at Tylney Park Golf Club in Hampshire.

-

How Many Majors Will Masters Champion Rory McIlroy Win In His Career... And Which Is Next?

How Many Majors Will Masters Champion Rory McIlroy Win In His Career... And Which Is Next?Rory McIlroy completed the Career Grand Slam in dramatic fashion at The Masters, but how many Majors could he go on to win in his career (and which comes next)?

By Barry Plummer Published

-

'You Can't Win Them All If You Don't Win The First' - McIlroy Grand Slam Odds Shorten After Masters Victory

'You Can't Win Them All If You Don't Win The First' - McIlroy Grand Slam Odds Shorten After Masters VictoryMcIlroy completed the Career Grand Slam after winning The Masters, with his odds of claiming the Grand Slam in 2025 slashed after his Green Jacket victory

By Matt Cradock Published