Old Tom Morris: A Golfing Titan

More than 200 years on from the birth of Old Tom Morris, we reflect on the long life of a man instrumental in shaping the game of golf as we know it.

The 16th of June 2021 marked the 200th anniversary of the birth of one of the most iconic figures in the history of golf. Old Tom Morris was a champion golfer, a pioneer in course design and of greenkeeping practices. His fame brought golf into the public eye. Framed by cap and beard, his face remains one of the most recognisable in our sport.

The year 1821 was a seminal one in the history of golf in St Andrews. It was the year James Cheape of Strathtyrum purchased the links for the golfers, to prevent rabbit farmers taking over. And, on the 16th of June, Tom Morris was born in a weaver’s cottage at the links-end of North Street.

From the outset, golf was a feature in Tom’s life. He was christened “Thomas Mitchell” by a golfing minister from Perth, the Reverend Dr Buist, and was soon swinging a club.

“I wad be driving a stane wi’ a bit o’ stick as sune’s I could walk,” he later recalled.

School was a relatively brief affair for Tom, and little is known of what he did between leaving in 1831 and going to work with the master ball-maker and caddy Allan Robertson towards the end of the 1830s.

Tom was taken on as an apprentice and Robertson taught him to make a “feathery,” and also how to play the game of golf on the links.

Tom spent four years as an apprentice then became a journeyman, making balls for Robertson, caddying, playing matches and all the while improving at the game. By 1842 he was a rival to his supposedly unbeatable mentor.

Get the Golf Monthly Newsletter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

Successes on the links

A group of the early professionals including Tom Morris and Allan Robertson (fourth and third from the right)

Robertson and Morris won a series of foursomes matches together, forging a formidable reputation. But their partnership and friendship ended when Robertson spied Morris out on the links playing with a rubber “gutty” ball. A new invention made of “gutta percha,” it was more durable and cheaper than the feathery. Robertson was dismayed at the arrival of the gutty as it threatened his livelihood. It was no consolation that Morris had simply borrowed the gutty from a playing partner having run out of balls himself. Robertson cried out to Morris, never to show face again, and that was the end of it. Morris took his wife and young son Tommy across the country to Prestwick where he had accepted a job as “Keeper of the Green.”

As a player Tom was highly skilled, though not infallible. In his early matches with Robertson, he developed a reputation for fragility from close range. An R&A member once sent Tom a postcard addressed simply to, “The Misser of Short Putts, Prestwick.” The postman was in no doubt of where to take it.

But Tom had a slow, smooth and consistent swing, a cool temperament and a fiercely competitive nature.

Morris continued to enjoy successes in money matches and, in the 1850s, established a tremendous rivalry with Willie Park.

Hailing from Musselburgh and born in 1833, Park was the pick of a fine selection of players from the “honest toun.”

Morris and Park contested a series of high-stakes, marathon matches through the 1850s and 60s which attracted large crowds and some significant betting.

In their 144-hole match over Musselburgh, St Andrews, North Berwick and Prestwick in 1856, the stake was £100. To put this in context – when Morris won his fourth and final Open Championship in 1867, the winner’s prize was £7.

In 1860, Lord Eglinton and Colonel James Ogilvie Fairlie decided to host a professional tournament to raise Prestwick’s standing as a club. A Championship Belt would be on offer to the victor.

It was Tom’s great rival Park who came out on top in that first Open Championship, but when The Open was contested a second time at Prestwick in 1861, Tom defeated Park by four. In 1862 he beat his rival by an astonishing 13 strokes, a winning margin that’s never been equalled.

Tom won again in 1864 and for a final time in 1867. He played in 35 of the first 37 Open Championships and recorded a top-10 finish as late as 1883, then aged 62. His last appearance came in 1896, just days before his 75th birthday.

Tragedy

Young Tom's grave in St Andrews

By the time of his last Open win, Old Tom was already being pushed hard by his young son Tommy who won a professional event at Carnoustie in 1867.

A year after Old Tom had become (and remains) the oldest Open winner, aged 46, his son Tommy became the youngest champion, aged 17.

Tall and strong, Tommy played with power and finesse and had a natural touch around the greens.

Tommy won The Open again in 1869 and for a third time in 1870, thereby winning the Championship Belt outright. In 1872 he won a fourth straight Open, (the championship wasn’t held in 1871.) Although it wasn’t ready for 1872, Young Tom’s name was inscribed on the new trophy – a Claret Jug, presented first to Tom Kidd in 1873.

Unfortunately, Tommy’s life was a tragically short one. His wife died in childbirth in September of 1875 and, before the year was out, so had Tommy.

Keeper Of The Green

The 17th at Prestwick - Originally the 2nd on Old Tom's 12-hole layout

For all Old Tom’s skill as a competitive golfer, his contribution to golf was far more than just as a player.

After moving to Prestwick in 1851, Tom laid out a 12-hole course over the links there. He completed much of the construction work himself, gaining (at that time) unparalleled knowledge of golf course design that he would put to good use over the next 50 years – Designing, or adding his touches to some of this country’s best-known courses, including Muirfield, Moray, Lahinch and Royal North Devon.

After moving his family back to St Andrews in 1864, accepting a job as custodian of the links for the R&A (a post he would hold until his retirement in 1904,) Tom quickly began to make improvements to the links.

The changes he made between 1864 and 1879 were significant in establishing the Old Course we know today.

The techniques Tom employed influenced greenkeeping practices going into a new century. He used sand to level surfaces and to act as a top-dressing, he used push mowers on the greens and began to manage bunkers rather than leaving them alone as simply craters in the course.

Victorian Icon

Old Tom in 1901

Tom became the face of golf in the second half of the 19th Century. The late Victorians enjoyed the idea of celebrity and, with his distinctive look and obvious skill, Old Tom’s battles with Park and exploits with his son, captured the public’s attention. Like W.G. Grace did for cricket, Old Tom brought the idea of golf to a far wider audience.

It helped that, by all accounts, Tom was a great man as well as a great golfer.

In his “The Book of Golf and Golfers,” Horace Hutchinson described Old Tom as, "One of the most remarkable and best of men.” He continued, “Morris has been written of as often as a Prime Minister, he has been photographed as often as a professional beauty, and yet he remains, through all the advertisement, exactly the same, simple and kindly."

Acknowledgement of his qualities as a human as well as a golfer are many and varied – He was first honorary member of the New Golf Club, he was granted a testimonial fund and his portrait was commissioned by the Royal & Ancient Golf Club, he was even selected by the St Andrews Presbytery as their representative at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1896. He was a much-loved son of St Andrews.

When Morris died, in 1908 at the age of 87, the funeral procession extended the entire length of South Street. Fellow professional Andrew Kirkaldy described, "a cloud of people," and said, "there were many wet eyes among us, for Old Tom was beloved by everybody."

202 years after his birth, Old Tom Morris remains one of golfing history’s most recognisable figures. His deeds on the course, playing, building and maintaining, did a huge amount to push golf forward into the 20th century, setting the sport on the path to becoming the one we enjoy playing and watching today. We should all doff a flat cap to golfing pioneer Old Tom Morris.

Old Tom and The Open

When the first Open was contested at Prestwick in 1860, the field comprised just eight players.

This was partly because invitations had only been sent to 11 clubs and partly because no prize money was on offer, save for side wagers. In addition, many thought they stood little chance against Tom Morris and Willie Park. They were right.

There were 12 players when Tom was winner for the first time in 1861 and when Morris won again by 13 strokes in 1862, many took it as confirmation that he had truly taken on the mantle of best of the best, following the death of the great Allan Robertson in 1859.

The 1881 Open provided evidence of the grit and determination of Old Tom. Aged 60, he was one of only eight players to finish at Prestwick in gale-force winds and conditions so horrendous that nearly 200 fishermen lost their lives at sea on that day.

It was fitting that the 1896 Open, Old Tom’s last start, witnessed the first success of another legend of The Open. Harry Vardon triumphed in a playoff over great rival J.H. Taylor at Muirfield that year. Vardon went on to win a record six Opens – joining Old Tom as one of the game’s greatest icons.

Fergus is Golf Monthly's resident expert on the history of the game and has written extensively on that subject. He has also worked with Golf Monthly to produce a podcast series. Called 18 Majors: The Golf History Show it offers new and in-depth perspectives on some of the most important moments in golf's long history. You can find all the details about it here.

He is a golf obsessive and 1-handicapper. Growing up in the North East of Scotland, golf runs through his veins and his passion for the sport was bolstered during his time at St Andrews university studying history. He went on to earn a post graduate diploma from the London School of Journalism. Fergus has worked for Golf Monthly since 2004 and has written two books on the game; "Great Golf Debates" together with Jezz Ellwood of Golf Monthly and the history section of "The Ultimate Golf Book" together with Neil Tappin , also of Golf Monthly.

Fergus once shanked a ball from just over Granny Clark's Wynd on the 18th of the Old Course that struck the St Andrews Golf Club and rebounded into the Valley of Sin, from where he saved par. Who says there's no golfing god?

-

'This One Is Just As Much His As It Is Mine' - Rory McIlroy Pays Emotional Tribute To 'Big Brother' Harry Diamond After Historic Masters Win

'This One Is Just As Much His As It Is Mine' - Rory McIlroy Pays Emotional Tribute To 'Big Brother' Harry Diamond After Historic Masters WinThe 2025 Masters champion couldn't hold back the tears when discussing the importance of his relationship with caddie Harry Diamond

By Elliott Heath Published

-

Rory 2.0 Was Born At The 2025 Masters... McIlroy Is Now Free Of His 11-Year Major Burden

Rory 2.0 Was Born At The 2025 Masters... McIlroy Is Now Free Of His 11-Year Major BurdenThe Northern Irishman dug deeper than he ever had to get over the line and finally seal the missing green jacket to his career grand slam puzzle

By Elliott Heath Published

-

Quiz! How Much Do You Know About Ben Hogan?

Quiz! How Much Do You Know About Ben Hogan?Ben Hogan was one of the greatest golfers in the history of the game. He was a brilliant swinger of the club and is an icon of the sport. How much do you know about him? Test yourself here…

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

Quiz! Golf In The Roaring 20s – How Much Do You Know About Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones?

Quiz! Golf In The Roaring 20s – How Much Do You Know About Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones?Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones were the standout star golfers of the 1920s. How much do you know about their golfing careers? Test yourself with this quiz

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

How Far Did Old Tom Morris Drive The Golf Ball?

How Far Did Old Tom Morris Drive The Golf Ball?Old Tom Morris became a golfing legend in the second half of the 19th century, but how far could he hit the golf ball?

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

Injury, The Yips And No Form... How Ben Hogan Almost Pulled Off The Unthinkable In His Last Masters Appearance

Injury, The Yips And No Form... How Ben Hogan Almost Pulled Off The Unthinkable In His Last Masters AppearanceAt Augusta National in 1967, 54-year-old Ben Hogan rolled back the years with an incredible back nine of 30 in the third round of his final Masters

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

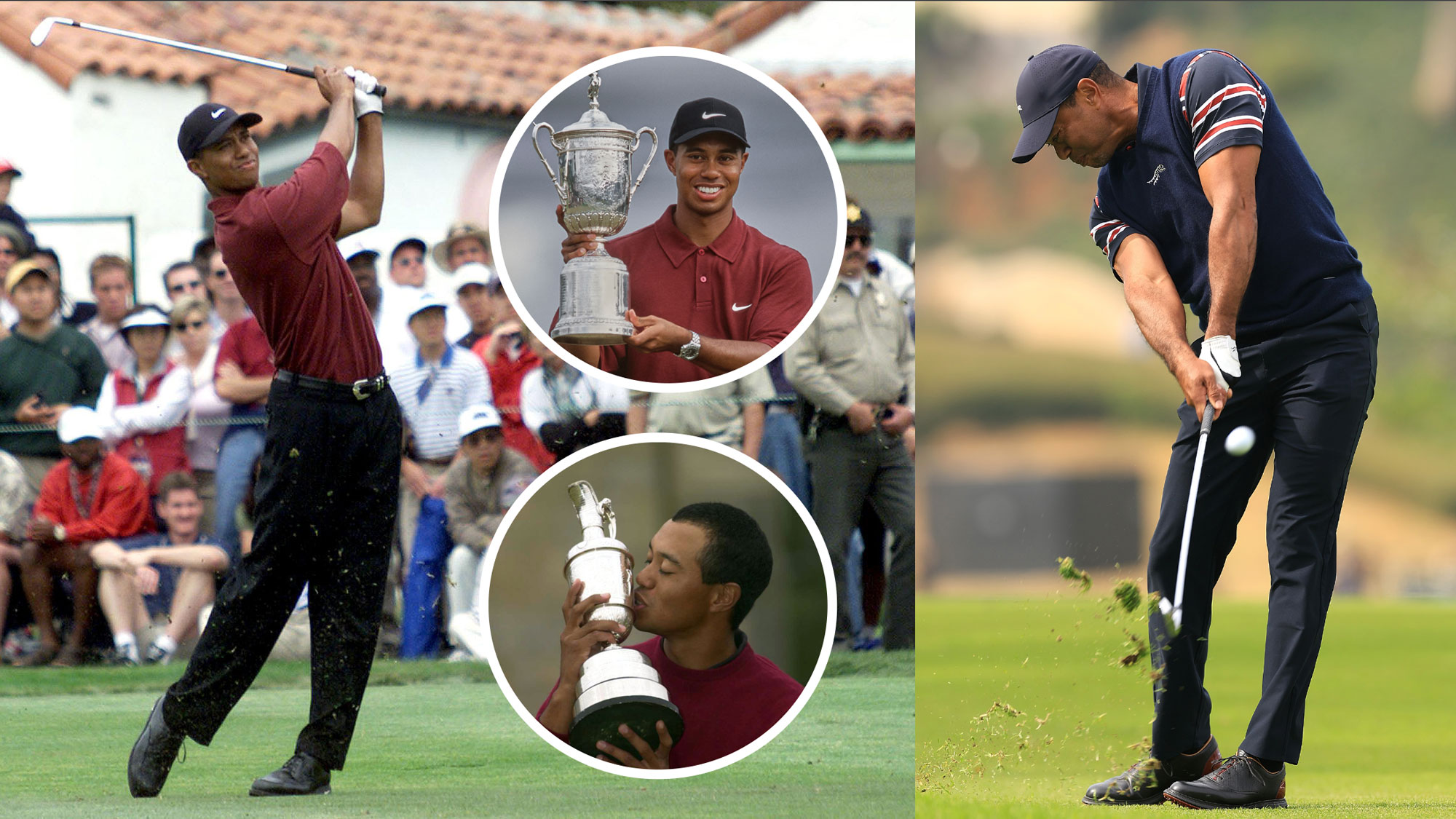

How Would The Unstoppable Tiger Woods Of 2000 Get On Against Today's Best Golfers? We've Crunched The Numbers To Find Out...

How Would The Unstoppable Tiger Woods Of 2000 Get On Against Today's Best Golfers? We've Crunched The Numbers To Find Out...In 2000, Tiger Woods played golf that seemed, and was at times, out of this world. Was it the best anyone has ever played? How would it compare to the best of today?

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

Seve Or Arnie, Who Did More For The Modern Pro Game?

Seve Or Arnie, Who Did More For The Modern Pro Game?Both men were inspirational, and both played a key role in the development of the professional game during the second half of the 20th century.

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

It Only Took 19 Play-Off Holes... The Amazing Story of Hale Irwin's Record-Breaking 1990 US Open Win

It Only Took 19 Play-Off Holes... The Amazing Story of Hale Irwin's Record-Breaking 1990 US Open WinHale Irwin came through a play-off to become the oldest ever US Open winner in an unlikely and highly memorable contest at Medinah

By Fergus Bisset Published

-

Woods Vs Mickelson – The Numbers Behind One Of Golf’s Great Rivalries

Woods Vs Mickelson – The Numbers Behind One Of Golf’s Great RivalriesWe take a look at the careers of two legends from the last 35 years of golf and compare some of the numbers behind their success.

By Fergus Bisset Published